Cyborg obsolescence: Who owns and controls your brain implant?

Medical breakthroughs, bionic tech, and cyborg bodymods sound like fun and games until enshittification hits your eyes, ears, and cortex

Digital 'ownership' and obsolescence

In 2009, readers of Kindle ebooks were startled to find that Amazon had remotely wiped some of their purchased books without notice. It was like Amazon had snuck into their house at night and sneakily pulled a couple books from the bookshelf. The books in this particular case? Orwell's 1984 and Animal Farm (felt a bit ironic at the time). Back then Amazon settled a class action lawsuit swearing not to remotely take back purchased ebooks under normal circumstances.

In 2015, Microsoft finally stopped supporting its Zune music player. Even though many songs in a user's library would still be playable on the device after support ended, users were frustrated to find out that other songs they had purchased would no longer play because those songs were protected by DRM (digital rights management) software.

In 2019, Microsoft shut down its ebook library. The books users had purchased and downloaded onto their devices? Locked out. Inaccessible due to DRM. Microsoft did offer a refund for the books they removed access to, but it's a stark reminder that a lot of the things we buy aren't actually bought and owned, but rather licensed to us, and often in such a way that the rug can be pulled out from under us at any time. It's as if the bookshelf in your home library were still sitting there, but now with an impenetrable lock keeping you from your beloved books.

Similar things happened when Samsung shut down their Video and Music Hub (users losing access to content they had purchased, with DRM preventing transfer to other devices), when HTC phones discontinued the HTC Watch application (users lost access to purchased movies and shows), and when Sony shut down their OnLive gaming service (taking users' games and data with it and no refunds offered)1.

It's easy to forget that for all that digital media and software has made our lives more convenient, it comes with costs we often don't acknowledge (or for many users, may not even realize!).

The button for Kindle books on Amazon's website says "Buy Now", but really it should perhaps say "Purchase a license to get access to a DRM-locked copy of this media that you don't own, have limited use of, and which we can potentially remove at any time."

When you buy a physical book or a music CD, you gain ownership over that thing. Not the ordered set of words or recorded sounds inside (that's protected by copyright law), but the actual physical copy in your hand? That's yours. In the U.S., that means you have the right to, say, sell it to someone else (the legal first-sale doctrine). But digital goods? Not so much. You own a lot less than it seems, but that's easy to forget until a bunch of stuff you've paid for is no longer accessible just because a company decided to change their rules or flip a server switch.

For the most part, this is just a frustration of modern digital life. I hate it, but it's hard to avoid, just like the subscription-based software-as-a-service (SAAS) model that tech companies love so much now2. Unless you put in ungodly time and effort to stick to open source software, you just have to accept that digital life gives users much less control over their fate than physical things do.

Except that nowadays, everything is becoming digital.

You buy a car with heated seats, remote start, and a powerful engine, but you can't access the heating, the remote start, nor the car's full acceleration unless you pay extra or add a monthly subscription.

You buy a printer but it refuses to print even when there's plenty of ink left in the cartridge because, sorry, the software says it's time to buy a refill (oh, and some printers won't let you scan a document if the unrelated ink needs refilling)

You buy a smart fridge and then one day the built-in app controls are disabled and your kitchen retroactively loses some functionality at the whims of Best Buy.

You buy a smart home platform, then Lowes shuts it down, bricking many devices that had no simple migration path to another ecosystem.

You buy an automatic pet feeder that later stops dropping the scheduled pellets for your pet kitty because the company goes under and apparently the device needed to phone home to function (the company first told users they needed to start paying a $30/year subscription to keep their device working).

You buy a John Deere tractor for your farm, but find it nearly impossible to repair it on your own because the company installed software that makes you pay them for repairs.

Cyborg obsolescence: When your bionic eye shuts down

"Barbara Campbell was walking through a New York City subway station during rush hour when her world abruptly went dark," begins a story not long ago in IEEE Spectrum (Strickland & Harris, 2022). For years, Campbell had been walking around with a medical device implanted in her retina to compensate for a genetic condition that affected her sight.

Retinitis pigmentosa is a genetic disorder causing one of the more common forms of vision loss, specifically loss of peripheral sight eventually leading to 'tunnel vision' (you can see what it might look like in my YouTube lecture about eye function from my sensation & perception course).

In the early 2000s the company Second Sight Medical Products developed an implantable prosthesis for the retina to help improve vision in those with retinitis pigmentosa. A bionic eye, basically. It consisted of a digital camera mounted on some glasses frames and a processor that translated that into signals that could be sent to the surgical implant in the retina, which in turn consisted of just 60 little electrodes to send jolts of activity to retinal cells.

We have hundreds of millions of photoreceptors in the retina (not to mention all the other neurons in the retina that process and pass along that info to the brain) so the 6 by 10 grid image produced by these 60 electrodes is, well, extremely low resolution, but enough to provide some gross information about objects off in the periphery. Think of it like a (very basic) cochlear implant for the eye.

They called it the Argus II and after some early testing in Mexico, it was implanted in 30 patients enrolled in a U.S. clinical trial with somewhat promising results (alongside some significant side effects). The FDA later approved it for use in up to 4,000 people a year in the U.S. under a humanitarian device exemption (in 2013, it was priced around $150,000 for the device alone, with total costs closer to $500,000 according to one user).

However, as IEEE documents, in 2019 "Second Sight sent Argus patients a letter saying it would be phasing out the retinal implant technology to clear the way for the development of its next-generation brain implant for blindness, Orion, which had begun a clinical trial with six patients the previous year."

In 2020 the company stopped providing support for the device. By March 2020 the majority of Second Sight's employees were gone and its equipment and assets were auctioned off, all without notifying any of the patients what was happening. "Those of us with this implant are figuratively and literally in the dark" wrote user Ross Doerr. The company nearly went out of business in 2021 despite an IPO focused around hopes of developing a new brain implant technology, Orion, to bypass the damaged eye altogether.

Meanwhile, though, more than 350 blind and visually impaired users had found themselves in a world where something that had become part of their body could suddenly shut down, irreparably, based on the whims or luck of a for-profit company that might decide at any time another angle is more promising than the tech already installed in some user's bodies.

In the case of Second Sight and the Argus II users, thankfully a merger in 2023 promised some further technical support for their retinal devices, though the new company is mostly focused on the Orion brain implant (Harris, 2023).

Cochlear implants and "compulsory upgrades"

What I'm calling cyborg obsolescence isn't just an issue for experimental technology like the Argus II. Cochlear implants are much more familiar and everyday medical technology at this point, an electronic device to help with some forms of hearing loss. In this case, there's a microphone that picks up environmental sound, then a processor which sends digital signals to a series of electrodes implanted in the cochlea of the inner ear. The cochlea is where sound waves are normally transduced into patterns of neural firing that allow our brain to experience sound, just as the retina transduces light for vision. (I explain more on cochlear implants at the end of this YouTube lecture).

In 2023, medical anthropologist Michele Friedner wrote about children and others with cochlear implants that were suddenly losing support from the manufacturer:

"[A]fter four years of using and maintaining the cochlear implant—including the external processor, spare cables, magnets, and other parts—the family started receiving letters and phone calls from the cochlear implant manufacturer headquarters based in Mumbai. Their child’s current processor—a 'basic' model designed for the developing market—was becoming 'obsolete' and would no longer be serviced by the company. The family would need to purchase another one, said to be a 'compulsory upgrade.'" (Friedner, 2023)

Can't afford to upgrade? Too bad. Just like with iPhones, companies move on to new models and eventually stop servicing older generations of their technology. But a phone isn't an integrated part of our body (yet!). To have one of your sensory systems shut down because, well, the company that installed it has moved on to newer and better things feels pretty dystopian. More cyberpunk than cyborg chic.

"In one especially devastating case, a father lamented that his daughter, who had been doing well with her implant, could no longer hear since her device had become obsolete. All the gains she had made in listening and speaking had come to a standstill. She could no longer attend school because she could not follow what was being said and was not offered any accommodations. They were at an impasse: unable to afford a new processor and unable to imagine a different future." (Friedner, 2023)

Worse, in some cases the introduction of these implants means a child is never taught sign language, so if the cochlear implant stops working they are in a much worse position than if they'd never had the implant to begin with.

And it's not just cochlear implants and bionic eyes that are at stake here. A recent policy essay on Knowing Neurons investigated how these issues are affecting recipients of brain-computer interfaces, aka BCIs (Salem, 2025). BCIs are still largely the realm of experimental technology, prototypes used on animals or in clinical trials with a limited number of human patients.

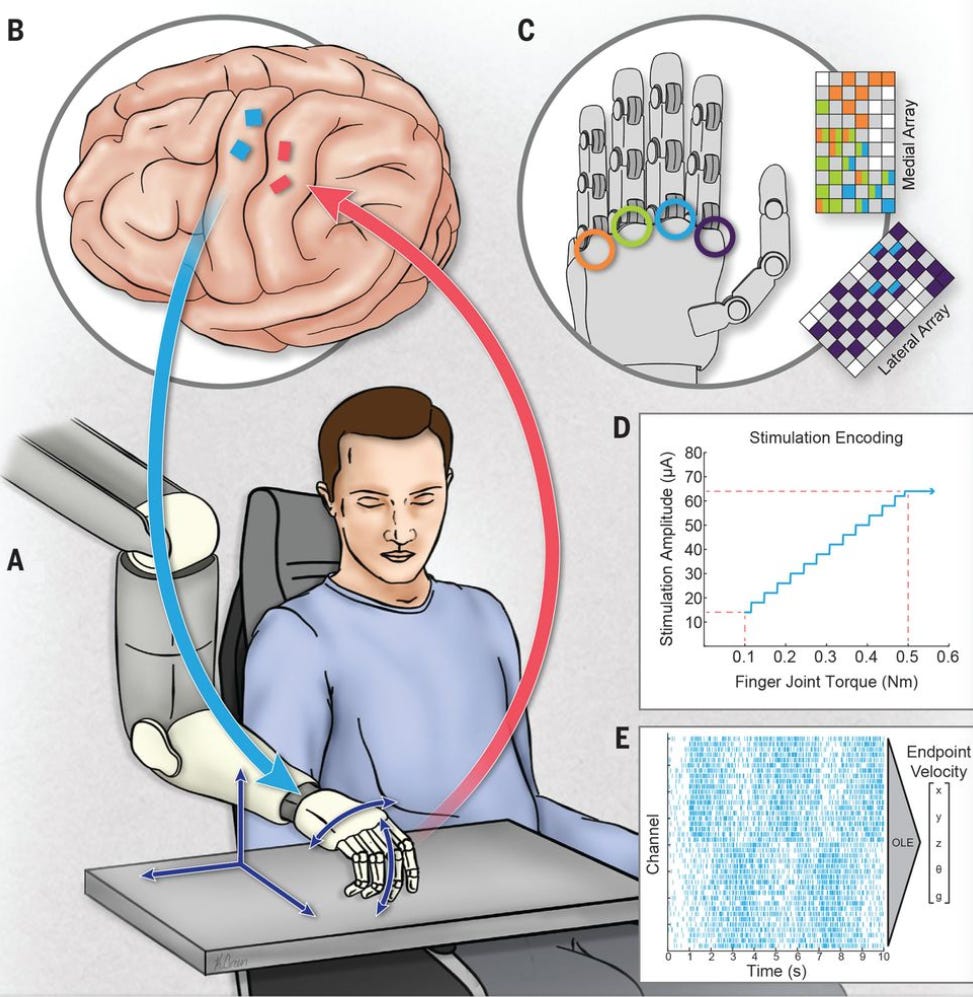

The amazing technology can feel a bit like a medical miracle, say by allowing someone paralyzed from the neck down to control a robot arm simply by thinking about the movement (i.e. activating chunks of neurons in the motor cortex by thinking about moving, which firing can in turn be picked up by the device and translated into instructions for a robotic limb)(e.g., Natraj et al., 2025). Other BCIs predict seizures, help with communication, and more.

But when clinical trials end, companies go under, or R&D moves in other directions, these medical miracles can turn into a medical curse for some patients left behind with brain implants that may no longer be supported. Sometimes that means losing functions you have gotten used to. In other cases, surgical removal of the device may be best (but surgery always comes with risk of complications).

Right now, there's little regulatory framework around such devices when it comes to discontinuation. "Ultimately, device companies have no obligation to continue offering access to their devices. Without standardized rules to protect future research subjects, we may end up in a world where people are treated unfairly, with some participants receiving long-term support and others being left without options" (Salem, 2025).

When that device has become inextricably part of you, an extension of your very perceptual experience or other cognitive function, then leaving support up to the beneficence of individual companies is a recipe for disaster. Regulation is needed, and it will become more and more of an issue as these technologies become more mainstream.

Enshittification for your body and brain

All of this intersects with the right-to-repair movement, DRM technology, data portability, and interoperability3. Just like farmers want the right to fix their own tractors and consumers want to be able to get their iPhone battery or screen replaced by a third party, users of medical devices, bionic sensory implants, and neuroprosthetics need a right to repair their devices or have them serviced by third parties, and this also means that the technology shouldn't be abandoned while locked behind unbreakable DRM, and that data from the software on these devices should be stored in such a way that others could take over and provide support after the original company stops doing so.

We need to think about (and ideally regulate) these things now to protect users of these devices against the inevitable when companies -- focused on the bottom-line and subject to the whims of the market -- disappear, choose to stop supporting a device, announce costly mandatory upgrades, or *shudder* institute subscriptions (maybe even ads!) for what used to be built-in functions.

When Google discontinues a service, it's a frustration. When your brain implant company discontinues a service, it's a violation of medical ethics and an assault on your bodily integrity.

And we know device companies are not always going to focus on medical ethics above profit. Look to Elon Musk's Neuralink, for example. While they brag about 'breakthroughs' (like a "monkey playing pong with [its] mind") that academic researchers had already accomplished decades earlier, they simultaneously are under investigation for causing needling suffering and death of tons of animals due to animal welfare violations caused by rushed testing.

"The investigation has come at a time of growing employee dissent about Neuralink’s animal testing, including complaints that pressure from Musk to accelerate development has resulted in botched experiments, according to a Reuters review of dozens of Neuralink documents and interviews with more than 20 current and former employees. Such failed tests have had to be repeated, increasing the number of animals being tested and killed, the employees say" (Levy, 2022).

Is this really the kind of company you want in charge of a device implanted into your very brain?

More importantly, even if the devices are totally safe and tested in the most ethical ways, what happens when companies move from providing a simple medical service (restoring a damaged sensory channel, say) to providing more complex functions like helping someone read, remember, concentrate, communicate?

Should these companies be able to decide willy-nilly to stop supporting some of those functions?

What about instituting a monthly subscription fee for cochlear implant customers who want the Pro Hearing Plan as opposed to Basic Hearing Plan, or subscriptions for TBI patients who want Standard Tier Memory Support instead of Introductory Tier?

How long until less well-off users are pushed into an ad-supported plan as the norm for those who can't afford the new raised monthly pricing on their brain implant? I guess when they all raise prices, you just have to choose between your Netflix subscription, your car's heated seats, your smart home security system, and the chip in your brain that lets you see, talk, or move.

Meanwhile, others have already started thinking about similar lifecycle issues for things like social robots (Kamino et al., 2024). As robots (including AI-powered robots) become entwined into our everyday lives as with, say, elderly users relying on a robot for activities of daily living, what happens when a company decides to brick the robot that's feeding and bathing grandma? What happens when the robot that grandma's been using for a couple years says it will stop wiping up after her in the bathroom unless she starts paying the new subscription fee they're instituting?

References

Flesher, S. N., Downey, J. E., Weiss, J. M., Hughes, C., Herrera, A. J., Tyler-Kabara, E. C., Boninger, M. L., Collinger, J. L., & Gaunt, R. A. (2021). A brain-computer interface that evokes tactile sensations improves robotic arm control. Science, 372(6544), 831-836. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd0380

Friedner, M. (2023, March 29). Who pays the price when cochlear implants go obsolete? Sapiens.org. https://www.sapiens.org/culture/planned-obsolescence-cochlear-implants/

Harris, M. (2023, August 15). Second sight's implant technology gets a second chance. IEEE Spectrum. https://spectrum.ieee.org/bionic-eye

Kamino, W., Sabanovic, S., & Jung, M. (2024). The lifecycle of social robots: Obsolescence and values in repair. 2024 33rd IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (ROMAN), 2147-2154. https://doi.org/10.1109/RO-MAN60168.2024.10731206 [PDF]

Levy, R. (2022, December 5). Musk's Neuralink faces federal inquiry after killing 1,500 animals in testing. Reuters. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/dec/05/neuralink-animal-testing-elon-musk-investigation

Natraj, N., Seko, S., Abiri, R. Miao, R., Yan, H., Graham, Y., Tu-Chan, A., Chang, E. F., & Ganguly, K. (2025). Sampling representational plasticity of simple imagined movements across days enables long-term neuroprosthetic control. Cell, 188(5), 1208-1225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.02.001 [PDF]

Salem, N. (2025, March 12). People living with experimental brain implants are unprotected by policy. It's a matter of human rights. Knowing Neurons. https://knowingneurons.com/experimental-brain-implants/

Strickland, E., & Harris, M. (2022, February 15). Their bionic eyes are now obsolete and unsupported. IEEE Spectrum. https://spectrum.ieee.org/bionic-eye-obsolete

Footnotes

Speaking of video games, a couple weeks ago a European petition called Stop Killing Games reached the necessary threshold of 1,000,000 signatures. What's it about? Many modern video games "phone home" to company servers, even for single-player play that shouldn't require any internet connection, and the games are designed in such a way that once the publisher stops supporting the game actively, it becomes completely unplayable. Bricked. The product you purchased has been remotely disabled simply because the company has moved on to new, shiny things. The petition is to get regulatory protection for consumers such that video games must remain in a working state even when the company moves on to other things.

It used to be you'd buy a copy of some software one time (on a disk or downloaded), install it, and the software would keep working in that same state for as long as you wanted. Yes, you might be stuck with the older functionality of MS Office 2013 rather than the newest features, but your software didn't disappear or stop working the moment you stopped paying an ongoing subscription at whatever price the company dictated each year (ala Office 365). SAAS has plenty of beneficial use cases, but boy oh boy is that paradigm amazing at milking users for more and more money for things they used to be able to just buy once and enjoy.

I talked about some of these issues in my recent post on enshittification.