How college professors are adapting to rampant AI cheating

Are blue books and oral exams the answer?

In the wake of LLM popularity, college is changing rapidly and both professors and students have been left flailing.

Imagine being a college student on your first day of a new semester. One professor says that using generative AI is cheating, while the next says you will be using it extensively in the course, and yet another does not mention it. You are told you will be punished if an AI detector classifies your assessments as AI-generated. Some professors encourage you to use a grammar app to improve your writing, but others tell you that doing so counts as cheating. At home, one parent worries AI will atrophy your brain and abilities, while the other tells you that you need to learn prompt engineering to have any hope of landing a job in the new AI-infused economy. Pundits in the media say AI makes college obsolete, social media influencers advertise apps that can complete all your papers and online tests, and meanwhile some of your friends are showing off creative applications of AI for fun while others say AI will destroy the world. If you were a college student, you would probably find yourself confused, perhaps excited or nervous about this new technology, and likely unsure of where it fits in your future.

That quote is how I started a journal article I recently published in Teaching of Psychology (Stone, 2025; free PDF). The 700+ college students I surveyed reported a lot of uncertainty about the role of AI in their education and future. They're both nervous and excited about the new technology, but leaning nervous: will AI increase inequality? Will it rob them of the jobs they hoped for after graduating1?

They're getting mixed messages, contradictory advice, and different policies from all around. The students in my study reported that they're more likely to use AI in what they consider ambiguous use cases (unsure if it's allowed or not) than in ways that are outright banned. Even so, more than 40% of the 700+ students I surveyed admitted to using AI to cheat in this dataset from a year ago.

And in a more recent follow-up study involving 500+ students I found that had increased to more than 60% of students admitting to cheating with AI. Some college students have always cheated, but the scale of cheating with AI is massive.

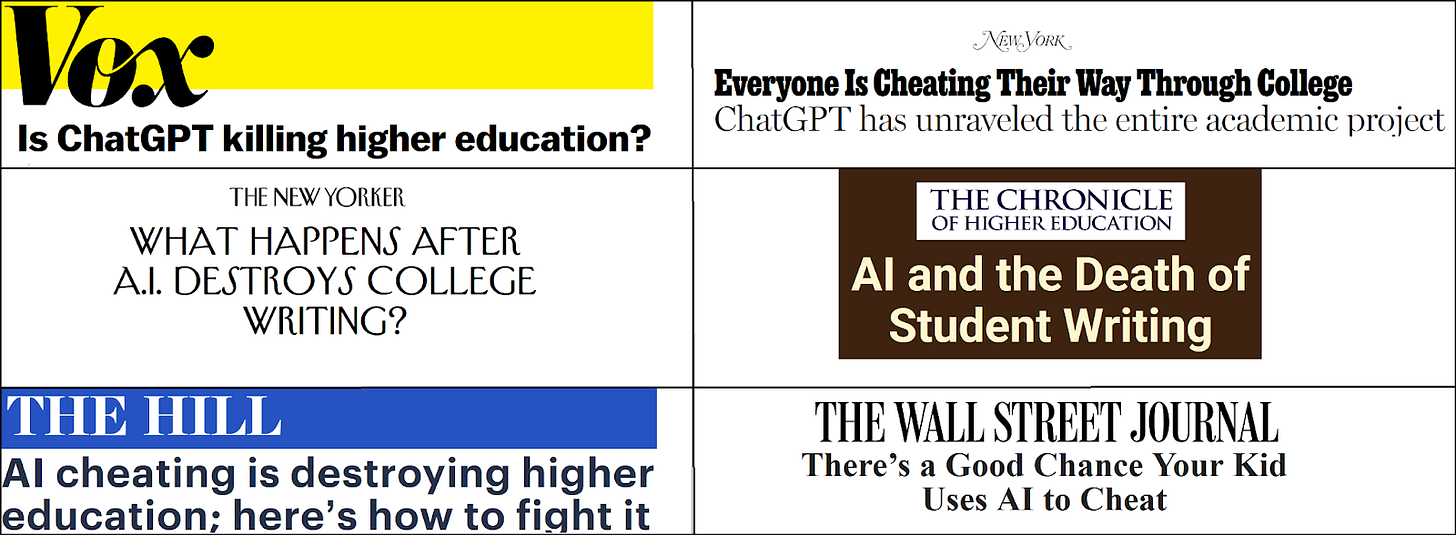

And it's no secret. Popular media outlets have been ringing the alarm bells.

"Everyone is cheating their way through college. ChatGPT has unraveled the entire academic project" (Walsh, 2025)

Is ChatGPT killing higher education? AI is creating a cheating utopia. Universities don't know how to respond" (Illing, 2025)

"The cheating vibe shift: With ChatGPT and other AI tools, cheating in college feels easier than ever -- and students are telling professors that it's no big deal" (Stripling, 2025)

In a conference not long ago, OpenAI shared that their usage spiked during the school year and dropped off massively in the summer. This past spring semester, right around finals time, AI companies started giving away free premium subscriptions to college students (e.g., Gemini Advanced, ChatGPT Plus, Super Grok). Meanwhile, last month the biggest AI apps in China shut down some of their features during the week of nationwide college entrance exams2.

Detecting AI usage

One reason cheating is so rampant right now is because it's really hard to detect, especially in a conclusive way. In the past, when a student copy/pasted from another source verbatim, it was often easily detected with plagiarism scan tools like TurnItIn. When a student used a word spinner to thesaurisize copied material, tortured phrases would set off alarm bells for any grader ("left hemisphere of the brain" becoming "side circle of the mind"). But with AI, you get new and unique sentences in perfectly standard English. Maybe it's got some tics like heavy use of em-dashes or a tendency to "delve into" topics, but those signals are hardly strong enough evidence to convict someone of academic dishonesty.

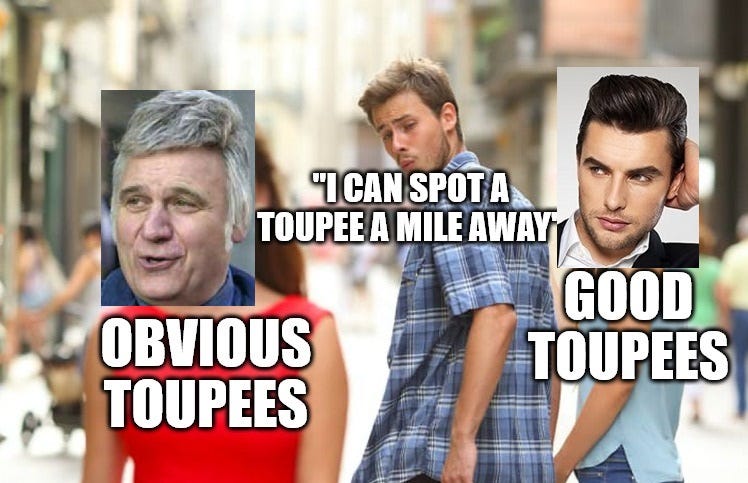

Late last year, Chris Ostro and Brad Grabham at UC Boulder provided a nice summary of some of the existing literature on AI detection. For example, one study found that 94% of AI-generated college writing goes undetected by instructors (Scarfe et al., 2024) while getting higher grades than real student work. Another study showed that university graders detected barely more than half of AI-written assessments (Perkins et al., 2024). Some professors may think they can spot AI a mile away, but we must always beware the toupee fallacy.

Meanwhile the media has picked up on stories of students facing false accusations of cheating with AI. Indeed, in my own study, 11% of students reported being falsely accused of cheating with AI (and first-gen students may have been more likely to receive such accusations; Stone, 2025). Some early work suggested automated detectors might have a bias against English-language learners (Liang et al., 2023), though more recent and higher-quality work didn't find that (Jiang et al., 2024). Regardless of whether some students are more likely to be falsely accused, the fact is that such accusations damage the student-instructor relationship, but they're unavoidable when detection is imperfect (to say the least).

Meanwhile, we might hope for automated detection software to save us. Jiang and colleagues (2024) did find near-perfect accuracy by AI detectors (1 false positive in 2000 essays), but that was in a very circumscribed and standardized writing task (GRE essays) so such great performance is unlikely to generalize, not to mention this was detecting pure-AI writing vs. pure-human writing, rather than hybrid output or AI-generated work run through a "humanizing" app (as widely advertised to students on social media right now for defeating detectors). And indeed, Sadasivan and colleagues (2024) found that automated detectors are easily defeated with automated paraphrasing tools and that's unlikely to change any time soon. Frankly, it's just hard to detect AI-written work in an adversarial context.

Ostro and Grabham suggest a mosaic approach to AI detection combining automated tools with human judgment, but also suggest a tactic many instructors (like the awesome Anna Mills) have moved to: asking students to use Google Docs, Office365, Grammarly Authorship or other tools with version history tracking that can be shared with a professor to show a student's work on the document3. However, as Graham Clay showed back in February, agentic AI can already take on tasks like writing into and editing a document in a way that simulates human writing (video proof of concept here), so version tracking may become yet another detection arms race. Indeed, before long an agentic AI may soon allow a student to complete an entire online asynchronous course without ever lifting a finger (AI can log in, navigate the LMS system, load up the course materials, and complete assessments and activities).

Analog moves: Blue books, oral exams, and discussion

Meanwhile, many professors are addressing AI cheating by moving a lot of student work and assessments back into the classroom itself rather than having graded work done at home. The handwriting revolution, they say. In-person exams, blue book essays, short responses, and other hand-written assignments done in class under the professor's eye without digital tools4.

Honestly, that's been one of my major strategies for dealing with the huge pile of AI slop I found myself grading in 2023 and early 2024. It felt like a moral injury every time I put a bunch of time into writing comments on a paper I was confident was AI-generated, so I ditched some of the longer at-home writing (or made it worth less) and shifted to more in-class writing. I still retain some bigger out-of-class projects, but those integrate AI usage in ways that are guided and [supposed to be] documented properly.

Aside from lower-stakes practice, my quizzes and exams are back to pen and paper: as much as it feels like a waste of my valuable pedagogical time to silently proctor exams rather than administering them on a learning management system, I have shifted back to pen-and-paper quizzes and exams (with immediate feedback, though5). If I had fewer students, I'd probably be doing some oral exams as well.

For the most part, students have responded positively! In my anecdotal conversations with students, many of them are frustrated with their own self-control and inability to avoid using AI when it's available. But then they find themselves unmotivated to do the reading or put in the hard, effortful work to complete assignments themselves. They feel disconnected from their education, and it seems that forcing their hand by making them prepare for and complete assessments in class on their own is reconnecting them to their education in a more authentic way.

In-class discussion is another AI-free activity that students seem to get a lot out of. However, it's hard to scale up deep discussion in larger classes. You can do activities like think-pair-share where students reflect then discuss with neighbors then some groups share out to the class, but that's not usually a great fit for individual assessment (and many students can slip by without contributing).

My book club assignment

In my quest to adapt to the new AI landscape, I also came up with what I think is a really successful discussion activity that scales up to classes of any size while still allowing authentic assessment of each individual.

In my cognitive psychology course I assign Daniel Kahneman's (2011) book Thinking, Fast and Slow (and yes, I know it includes some individual results that didn't replicate, but we spend quite some time interrogating that, following up on the claims in the book, and learning about meta-science in the process). I used to assign students a big paper after they read the book, but in 2023 I started getting inundated with AI summaries of the book. At the time, these papers were error-prone and attributed terms and concepts to the wrong chapters, but as more recent LLMs gained the ability to scan the actual book PDF and not just regurgitate public internet reviews, it got even harder to be sure when I was reading a student's ideas about the book or an LLM's.

So I ditched the Kahneman paper assignment. In its place, I've been doing what I call book club assignments. Students are still assigned to read the book and make connections (with specifics) to other course content and applications in their own life, but now instead of doing so in a paper, they do so in a series of synchronous discussions with their peers (on Zoom, recorded to the cloud with a sharable link).

They have to upload scans of their prep work (notes on each chapter, more extensive prep for a selection of chapters they will lead the discussion on) and also submit a post-discussion reflection touching on what came up, where and why they changed their mind, and confidentially commenting on any peers who stood out as especially prepared or unprepared. Between that and me watching big chunks of the recording (on high playback speed), I can evaluate the quality of their emergent discussion, how deeply or superficially they can respond to their peers in the moment, and whether they are leading discussion of their chapters in a "reading this prepared AI-sounding summary" way or in a more authentic and dynamic way. And grading it takes less time than an equivalent number of papers.

I recently published a teaching case about this for the Society for the Teaching of Psychology where I explain some of the pros and cons of these book clubs. Yes, a student could get AI to summarize the assigned chapters ahead of time and transcribe those into handwritten notes, but those students seem to choke in the actual discussion.

I don't think long papers should be replaced completely (nor will the current solutions withstand AI forever), but right now I think it's helpful to consider alternatives that get at most of the same learning objectives while being less easily defeated by low-effort AI use.

And like I said above, students for the most part seem to respond positively when their ability to use AI is taken away! I think a lot of what's driving AI cheating is the same impulse driving addiction-like smartphone use in students: things like escape and avoidance conditioning in the form of negative reinforcement for behaviors that temporarily alleviate the bad feelings associated with procrastination, imposter syndrome, and hard work itself.

Just as many people today wish they had the willpower to put down their phone more easily, I think many college students right now deep down don't want to be using AI in low-learning ways (i.e. cheating, cutting out the real work), so when we take away the ability to do so, many seem to appreciate being forced to reestablish some authentic connection to their learning. My students have raved about the book clubs, praised the challenging in-class exams, and seemed to appreciate practice with low-stakes writing by hand. This is the case even in a course where we otherwise learn about, interrogate, and use AI!

Jason Gulya recently blogged about AI-free spaces, emphasizing that this doesn't mean a course is entirely AI free, but rather asking "whether we can cultivate AI-free moments in the classroom. [...] Sometimes, we'll need to use AI. Sometimes, we'll need to put AI down." As he points out, though, we can only keep the tech out so long before AI-powered pendants, rings, or smart pens become ubiquitous and hard to spot (alongside the existing scan most of us have started doing for smart glasses). Despite this Gulya remains somewhat optimistic, suggesting that we may be able to consensually co-create AI-free spaces with students where they have some buy-in and ownership over decisions like when and how AI is used.

I love this idea, though as usual with approaches requiring student buy-in it doesn't help as much with the students who see their education purely transactionally and don't really care.

For now, though, I'd like to at least try to reach the students that do care or can be nudged into caring.

References

Illing, S. (2025, July 5). Is ChatGPT killing higher education? Vox. https://www.vox.com/the-gray-area/418793/chatgpt-claude-ai-higher-education-cheating

Jiang, Y., Hao, J., Fauss, M., & Li, C. (2024). Detecting ChatGPT-generated essays in large-scale writing assessment: Is there a bias against non-native English speakers? Computers and Education, 217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2024.105070

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Liang, W., Yuksekgonul, M., Mao, Y., Wu, E., & Zou, J. (2023). GPT detectors are biased against non-native English writers. Patterns, 4(7), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2023.100779

Perkins, M., Roe, J., Postma, D., McGaughran, J., & Hickerson, D. (2024). Detection of GPT-4 generated text in higher education: Combining academic judgement and software to identify generative AI tool misuse. Journal of Academic Ethics, 22, 89-113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-023-09492-6

Sadasivan, V. S., Kumar, A., Balasubramanian, S., Wang, W., & Feizi, S. (2024). Can AI-generated text be reliably detected? arXiv Preprint. https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.11156

Scarfe, P., Watcham, K., Clarke, A., & Roesch, E. (2024). A real-world test of artificial intelligence infiltration of a university examinations system: A 'Turing Test' case study. PLoS ONE, 19(6), e0305354. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305354

Stone, B. W. (2025). Generative AI in Higher Education: Uncertain Students, Ambiguous Use Cases, and Mercenary Perspectives. Teaching of Psychology, 52(3), 347-356. https://doi.org/10.1177/00986283241305398 [free PDF]

Stripling, J. (2025, January 21). The cheating vibe shift. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/podcast/college-matters-from-the-chronicle/the-cheating-vibe-shift

Walsh, J. D. (2025, May 5). Everyone is cheating their way through college. New York Magazine. https://nymag.com/intelligencer/article/openai-chatgpt-ai-cheating-education-college-students-school.html

Footnotes

I've had to explain to countless students that if all they're doing in college is pressing a button to get AI to do their work, employers won't have any incentive to hire them when they graduate. After all, the employer can push that same AI button without having to pay another salary.

This may suggest top-down coordination from the CCP government. Tech platforms in China already do some coordinated censoring in early June around the anniversary of Tiananmen Square.

Some have argued that we're shifting the burden and responsibility for upholding academic integrity onto students in a way that's unfair.

Yes, some worry about eventual smart glasses as a cheating tool, but for now those are mostly easy to spot and require auditory cueing for many tasks. Smart watches may facilitate some forms of cheating right now, but are still a ways away from scanning a paper exam and outputting, say, an essay to transcribe into a blue book without getting spotted.

A trick I came up with years back for in-class exams: I put exam answer keys up front at a table away from the student desks, and once a student has handed in their exam, they can sit at that table and silently check the answers for any questions they wondered about. On the printout, I even write in a brief explanation paragraph for each question so that they can understand why the answer is what it is, and where they may have gone wrong if they answered incorrectly. It's drastically cut down on student follow-ups and office hours nitpicking about exam points, but more importantly, it helps cement student learning to get immediate feedback and correction.